One of the most important aspects of learning a language is knowing the items that make up its vocabulary, also known as its lexis or lexicon. If we add to this set of lexical items the necessary rules to combine them, i.e. the morphosyntax of a language, speakers will be able to communicate their ideas in a variety of contexts. But what items become part of the lexis, and how? In this article, we will discuss the concepts of lexical words, high-frequency lexis and low-frequency lexis and how they can help L2 learners incorporate new vocabulary.

What is a word?

A word can be defined as “a unit of expression which has universal intuitive recognition by native speakers, in both spoken and written language” (Crystal, p.521, 2011), but this is not so clear-cut. Generally speaking, it is a particular form of sound and writing connected to a mental concept. However, one word may have different forms (e.g. cat and cats), so when discussing vocabulary, linguists prefer to talk about lexemes, which are basic units of meaning in the semantic system of a language and what dictionaries usually list (ibid, p. 276.)

To complicate things further, the sound-meaning relation is arbitrary, so there are words with the same sound and different meanings (write and right) and words with the same meaning and different sounds (lift and elevator). The mental representation of the words we know, also known as the mental lexicon, varies and expands as we grow older and develop particular interests, professions, and so on (Fromkin, p. 37, 2011).

Photo by Snapwire from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/black-and-white-book-browse-dictionary-6997/

What does the lexicon include?

The boundaries of the lexicon range from a very narrow view, i.e. a list of indivisible forms distinct from morphology or syntax, to a very broad view, so that the smaller parts of a word (like the -ed ending for regular past simple verbs) are also included (Payne, p. 58, 2011). Regardless of the point of view preferred, an item becomes lexicalised mainly by its frequency of use. The more a word is repeated, the more habitual it becomes to speakers and the more entrenched it is in the lexicon.

But what determines the frequency in which words are used? Usually, frequency is determined by the word’s usefulness for expressing more common meanings. These words are the easiest to remember. However, they have also been worn down by their constant use and tend to be very morphologically irregular, such as the verbs go or be. Nevertheless, any item can be lexicalised if used for long enough, to the point that native speakers might “forget” the original form. For example, May God be with thee has become goodbye, which has in turn further been shortened to bye (íbid, p. 61-62).

New items (or words) can be incorporated into the lexicon of a language through various different methods, such as taking from other languages (something English is particularly good at). Other methods include coining new words by compounding, shortening and blending them, or simply inventing novel usages. Thus, the lexicon of a living, thriving language is always expanding and could be potentially infinite (íbid, p. 65).

Lexical vs grammatical words: content vs function

The main division inside a lexicon distinguishes between lexical (also known as content) words versus grammar (or function) words. Again, this is not such a well-defined distinction, but broadly speaking, lexical words have semantic content and refer to concepts that we can think of, such as objects, places, actions, attributes, and so on. On the other hand, function words specify grammatical relations and have little semantic content.

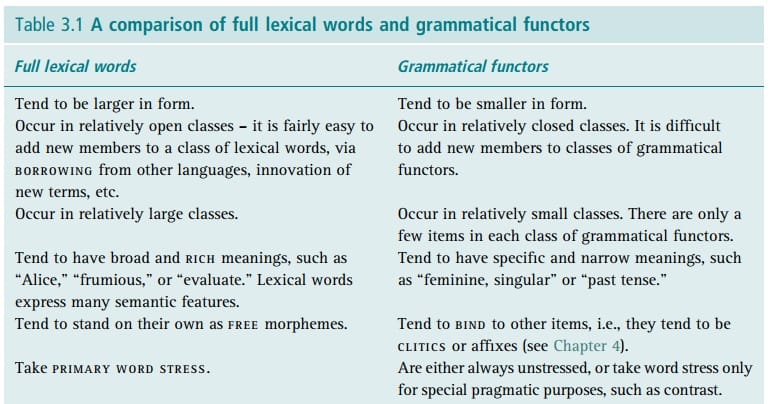

Taken from Understanding English Grammar: A linguistic introduction p. 67

If we delve a little deeper, lexical words tend to be longer and belong to relatively open categories since we can add new items to them through lexicalisation. They have rich meanings, express many semantic features, exist on their own as free morphemes, take primary words stress in spoken language, and are even capitalised in titles.

Conversely, grammar words tend to be shorter and belong to closed categories or classes (sets of words that share specific characteristics), since it is difficult to invent (for example) new prepositions. The struggle of creating genderless pronouns also illustrates this. Grammar words are rarely stressed and are written in lowercase in titles. In fact, there is even evidence that suggests the brain treats function words differently: people with brain damage and aphasia have a more challenging time understanding them (Fromkin, p. 40).

Finally, these two kinds of words have their own subclasses. Lexical words are usually classified into nouns (to denote objects or concepts), verbs (to denote actions or events), adjectives (to denote attributes) and adverbs (to denote how something is done). Grammar words include prepositions, auxiliary verbs (more limited in meaning than lexical verbs), pronouns, and conjunctions.

Photo by Tima Miroshnichenko from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-teaching-english-in-class-5427868/

How can high- and low-frequency words help L2 speakers learn vocabulary?

As a native speaker, your mental lexicon is expanding by being constantly exposed and immersed in the language. However, learning a new language implies incorporating an almost infinite set of lexical items. What is the best criterion to choose which words to learn, and how can we learn them? The answer seems to be the aforementioned frequency of a word. Taking this criterion into account, we can divide words into high-frequency lexis, mid-frequency lexis and low-frequency lexis.

Usually, the objective behind our learning will determine what to teach or learn. For example, a person who wants to become a lawyer should be acquainted with words that belong to that area of knowledge. If the purpose is more general, teaching frequently found words is a good idea since they tend to be more critical. They can, therefore, be more easily learnt and can help determine the difficulty of reading a given text (Vilkaitė-Lozdienė and Schmitt, p. 81, 2019).

The 20th century saw the development of vocabulary lists, such as Ogden and Richard’s Basic English List (1930) or the General Service List of English Words (GSL) of 2,000 words based on word frequency but also on other criteria. After a decline during generative grammar’s heyday, computerised corpora allowed linguists to calculate frequencies more precisely, as well as identify patterns. This opened many possibilities, especially for foreign language teaching.

A bone of contention when designing word lists seems to be which counting unit to use. On the one hand, word families (which include the base form of the word, its inflections and its main derivations) usually have been used, but not without their array of problems. Thus, lemmas or “words with a common stem, related by inflection only and coming from the same part of speech” have been proposed instead (ibid, p. 85).

Another important area to take into account is lexical coverage, which determines how many words of a reading or listening passage are necessary to know to understand them. When teaching, we should determine the percentage of words in a text a learner needs to know to understand it and then how many lexical items we need to reach that percentage. Numbers vary between an optimal of 8,000-word families and a coverage of 98%, and a minimal one of 4,000 to 5,000-word families, which cover 95% of texts.

As a result, the concepts of high-frequency, mid-frequency and low-frequency words have been devised to decide which words teachers should prioritise. High-frequency words provide the highest coverage, are the most useful and are relatively stable over time. Its number is still debated, however, ranging from 1000 words as an adequate goal for beginners to 3000 as an ideal figure. They can be taught through exercises, graded readers, flashcards or even target lists. To be able to read adult fiction, 6000 lemmas are necessary (íbid, p. 89).

Low-frequency vocabulary is more complicated to pin down. It has been suggested that 9,000+ word families should be labelled as low-frequency words based on the fact that the 9,000 most frequent word families in the British National Corpus frequency lists cover 95.5% of the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). This includes language that belongs to a specific field that is definitely useful for students of English for Specific Purposes, such as scalpel for surgeons. Rather than teaching all of these words, teachers should focus on learning strategies, i.e. guessing their meaning, drawing on word part knowledge, or using dictionaries.

Mid-frequency words is a relatively new term, and refers to words traditionally labelled as academic vocabulary and technical vocabulary. As stated earlier, people’s lexicon grows depending on their interests, jobs, etc. so it is more individual and specialised. Despite the lack of proper coverage, teachers can resort to lists of words for specific purposes or through extensive reading and graded readers.

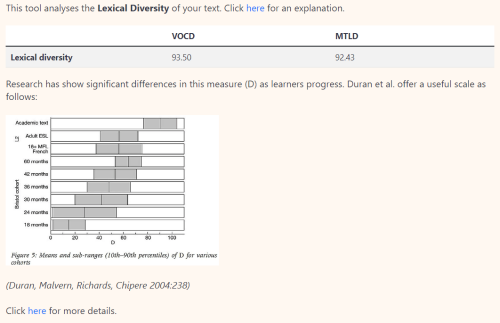

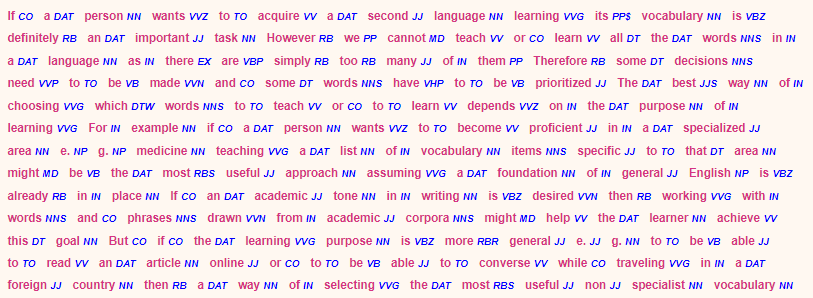

An example of Text Inspector analysing a passage from “Frequency as a guide for vocabulary usefulness: High-, mid-, and low-frequency words.”

How can Text Inspector help you?

In second language learning, frequency seems to be an adequate criterion to decide which words to focus on. For English, there seem to be around 3,000 most frequent word families that require our attention. Learners who want to be able to use and understand English in various spoken and written contexts should know the 9,000 most frequently used word families.

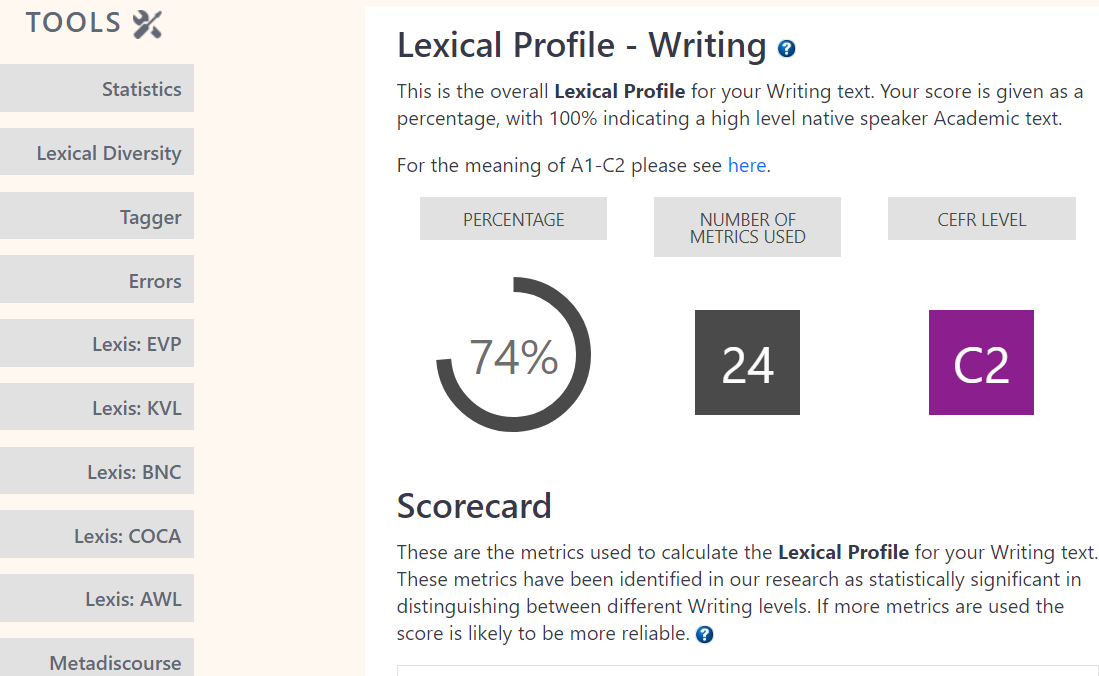

Frequency bands can also be helpful for language assessment. For example, to estimate learners’ lexical profiles and measure their lexical knowledge in L2 writing. The more high-frequency words they use in their writing, the higher their overall L2 command could be. Text Inspector measures the lexical diversity of your text, i.e. how many different lexical words it contains. A high score indicates that the text is more complex and challenging to read and that the author has a good grasp of the language.

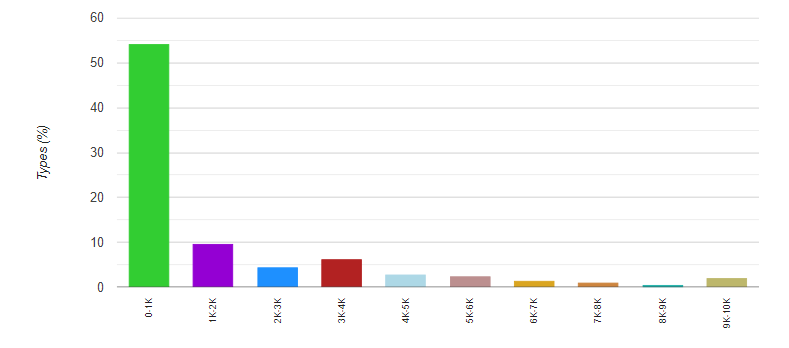

Text Inspector also refers to several different lists of words and corpora to provide a lexical profile of your text, including Cambridge’s English Vocabulary Profile, the British Council’s Knowledge-based Vocabulary Lists, the British National Corpus, the Corpus of Contemporary American English and the Academic Word List. It also uses the Parts of Speech Tagger to determine what classes of words (both lexical and grammar) are present in your text.

Using these metrics, teachers can measure the proficiency of an L2 learner’s written production or assess the level of authentic materials and adapt them for classroom use. If you are a student, you can check your written work and decide which high-frequency lexis, mid-frequency lexis and low-frequency lexis you should be incorporating into your lexicon in order to improve your proficiency in English.

An example of the BNC and COCA word frequency analysis

An example of the Parts of Speech Tagger

An example of the Lexical Profile of a text you can obtain with Text Inspector

Conclusions

Lexical items are basically the bricks that make up a language, and morphosyntax is the rule that determines how they are combined. Content (or lexical) words carry semantic meaning, and their creation and acquisition are essential for second language learning. Frequency is an excellent criterion to determine which words to teach in the classroom. Text Inspector enables you to analyse a text and obtain a detailed lexical profile, which has many applications both for teachers and learners.

References

- Aronoff, M., & Rees-Miller, J. (Eds.). (2020). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing.

- Crystal, D. (2011). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. Blackwell Publishing.

- Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2011). An lntroduction to Language. Cengage Learning.

- Payne, T. E. (2011). Understanding English Grammar: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, L., & Schmitt, N. (2019). “Frequency as a guide for vocabulary usefulness: High-, mid-, and low-frequency words.” In The Routledge handbook of Vocabulary Studies (pp. 81-96). Routledge.

- Webb, S. (Ed.). (2020). The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies. Routledge.

Contributed by Victoria Martínez Mutri

Victoria is a CELTA-certified English as a Foreign Language teacher with a background in Translation from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Fascinated by language since an early age, she’s particularly interested in the fields of Applied Linguistics and Sociolinguistics. She’s been researching and writing about gender-inclusive language since 2018. After graduating, she would like to obtain a Master’s Degree in Linguistics at a foreign university.

Share

Related Posts

How Can Text Inspector Help with Comparative Readability Analysis?

23 June, 2022

Texts have always played an important role in language learning, exposing the student to vocabulary, […]

Read More ->

Lexical Words and Language Learning

5 March, 2024

One of the most important aspects of learning a language is knowing the items that […]

Read More ->

What Are Discourse & Metadiscourse Markers?

23 June, 2022

Metadiscourse markers are words or phrases that help connect and organise text, express attitude, provide […]

Read More ->