How Can Text Inspector Help with Comparative Readability Analysis?

23 June, 2022

Texts have always played an important role in language learning, exposing the student to vocabulary, grammatical structures and real-life language use that could potentially improve their language level and fluency.

However, not all learning texts are suitable for the learner. Students should always have access to the right learning materials for their language ability and learning goals if they are to fulfil their potential in the classroom.

If not, the learner could become frustrated, lose motivation and feel disconnected from the content presented in the text, especially if they are a non-native speaker of English.

Responsibility for choosing the right reading material for learners mostly falls onto teachers who can often find the task somewhat challenging.

However, by using the professional and comprehensive tool created by Text Inspector, you can examine several texts and decide on the most suitable for your students quickly and easily.

In this blog post by Dr Irina Rets, we will discover the results of the study “Accessibility of Open Educational Resources: how well are they suited for English learners?” that used the Text Inspector tool and what it means for language learning texts.

Dr Irina Rets is a Research Associate at Lancaster University. She obtained her PhD in educational technology and applied linguistics from the Institute of Educational Technology at the Open University. In her PhD, she conceptualised and tested strategies for better accessibility of reading materials to international learners.

What problems can there be with difficult texts?

Reading, the process of obtaining meaning from a text is one of the major channels of information intake during learning.

Some readers may have a higher tolerance for uncertainty when dealing with a text they do not understand and continue to read, despite the challenges. However, generally frustrates the reader and creates a barrier to learn the content presented in the text.

Understanding and learning from a written text creates further vexing challenges for non-native readers of a given language.

The responsibility of choosing the right reading material for the learners mostly falls onto teachers. When choosing between several texts and deciding on the most suitable text for your learners, Text Inspector can help make this decision.

Using Text Inspector for a comparative readability analysis

The study of Rets, Coughlan, Stickler, & Astruc (2020) can serve as one example of how such comparative readability analysis can be carried out using Text Inspector.

The study was concerned with:

- whether reading materials in English from major Open Educational Resources (OER) platforms are accessible in their current form to non-native readers of English at lower levels of English proficiency.

- whether the educational level of the courses (eg. Introductory Level 1 courses, intended for the learners new to a subject; Intermediate Level 2 and Advanced Level 3 courses) make a difference in their accessibility

Procedure:

To answer this question, Rets et al. (2020) followed this procedure:

- They first downloaded reading materials from 200 Open Educational Resource (OER) courses found on two different platforms. They selected the Microsoft Word file option and then uploaded the files directly to the Text Inspector tool.

- For the purposes of the study, only the first 10,000 words were taken from the introductory sections of each selected course.

- All non-text elements (eg. illustrations, tables and bibliography) were removed as the tool doesn’t process such information.

Text Inspector uses the following readability assessment metrics in their text analyses.

Table 1. Applied readability metrics output by Text Inspector with their description

| Readability assessment metric | Characteristics | Interpretation |

| 1. Average sentence length | Average number of words per sentence | Having fewer words per sentence makes the text ‘easier’. Having shorter sentences is helpful because it reduces the amount of information one must store in their working memory during reading. |

| 2a. Type/token ratio (TTR) 2b. vocd-D 2c. Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity (MTLD) | Measures of lexical diversity, the proportion of unique vs. repeated words in the text | These measures refer to the degree of lexical variation in the text. The lower the measures are, the ‘easier’ the text. More repetition of the words already used in the text helps them to become more familiar. This means that it takes less time for a reader to process the words he/she already processed earlier in the text. |

| 3a. Words with more than two syllables (%) 3b. Average syllables per sentence 3c. Average syllables per word 3d. Syllables per 100 words | Measures of word length | The fewer syllables the words have (on average) in the text, the ‘easier’ the text. Shorter words with fewer syllables ‘give the mind much more to think about’ (Flesch, 1979, p. 22). |

| 4a. Flesch Reading Ease 4b. Flesch-Kincaid Grade 4c. Gunning Fog index | Formulas’ calculations are based on the analysis of word length vs. sentence length | 4a. Higher scores of Flesch Reading Ease indicate material that is easier to read. E.g., the scores 50.0-30.0 qualify as ‘College, difficult to read’ 60.0-50.0 correspond to 10th to 12th grade and ‘fairly difficult to read’ 70.0-60.0 – to 8th & 9th grade and ‘plain English’. 4b. The results of Flesch-Kincaid Grade correspond to the U.S. grade level. The lower the resulting grade is, the ‘easier’ the text. 4c. Gunning Fog index estimates the years of formal education a person needs to understand the text on the first reading. A score below 12 suggests a text that can be read widely by the public. A score below 8 indicates a very easy text. |

| 5. Noun elements per sentence | Average number of noun elements per sentence | Less nominalisation helps the text become easier to read. ‘Because nouns are merely names of things, they sound as if nothing is actually happening in the sentence’ (Flesch, 1979, p. 110). |

| 6a. Elementary lexis (A1-B1) 6b. Advanced lexis (B2-C2) | The proportion of lexis in the text that belongs to each language proficiency level in terms of CEFR | The more A1 lexis and the fewer C1 and C2 lexis the text has, the easier the text is. Text Inspector calculates this metric by using the Cambridge Learner Corpus (CLC). This is a collection of examination scripts written by learners at different proficiency levels. |

| 7a. 0-6K 7b. 6K-100K | Measures of word frequency. E.g., ‘1K’ means they are the first 1000 most frequently used/used words in English | The higher the percentage of the numbers before 6K, the more frequently used vocabulary the text includes and, thus, the easier the text is. Frequently used words tend to be recognised more rapidly and better recalled than words used less frequently. |

| 8. Logical connectives | A measure of text organisation, express relations between main clauses: e.g., ‘moreover’, ‘but’, etc. | More cohesive connectives between sentences in a text contribute to the text being ‘easier’. This is because they make the links between sentences more explicit. Comprehension of the text is fundamentally aided by coherence cues. |

| 9. Scorecard | An instant score that refers to the level of the text in terms of CEFR using all readability factors mentioned above | The Scorecard above B2 level indicates a difficult text that will be accessible to language learners of the highest level of proficiency. |

Analysis

In the analysis, the Scorecard (Variable 9 in Table 1) was examined then the number of courses that require more than the intermediate level of language proficiency was counted.

The descriptive statistics of the readability metrics produced by Text Inspector (Variable 1-8 in Table 1), were explored to identify if there was any difficulty progression between the different educational levels of the courses under study.

Then statistical approaches on comparing means were used to understand whether this difference was statistically significant.

Statistical analysis was also used to identify which readability metrics showed significant differences consistently between all educational levels in the course sample.

Results of the comparative readability analysis using Text Inspector

The scorecards automatically produced by Text Inspector for each course are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Courses under study (in %) in each scorecard

| Proficiency Level | Proportion of the courses under study |

| B1+ | 2% |

| B2 / B2+ | 7% |

| C1/C1+ | 35% |

| C2/C2+ | 56% |

As can be seen in Table 2, the minimum level of English proficiency required to be able to follow current OER courses was upper-intermediate (B2 and B2+) level in terms of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

In terms of the readability metrics vs. the educational levels, three variables showed statistically significant differences between all three educational levels of the courses under study.

These variables were:

- The measures of word length (words with more than two syllables, F (2, 147) = 22.16, p = .00)

- The amount of elementary lexis (A1, F (2, 147) = 15.41, p = .00) and advanced lexis (C1, F (2, 147) = 26.49, p = .00).

Comparison of the means of readability metrics between the levels showed that Advanced Level 3 courses are the most difficult to read of the three levels. The Introductory Level 1 courses are the easiest.

Table 3 below presents descriptive statistics for the readability metrics that demonstrate the progression of text complexity between the educational levels.

Table 3. Readability metrics: difficulty progression between the educational levels of the courses under study

| Variables | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Average sentence length (in words per sentence) | 20.96 | 2.29 | 22.88 | 2.8 | 23.07 | 2.69 |

| Average word length (% words with more than two syllables) | 15.56 | 3.4 | 18.31 | 3.17 | 20.55 | 5.22 |

| Low-frequency lexis 6K-100K (% words per text) | 19.86 | 5.23 | 21.18 | 3.99 | 21.36 | 2.80 |

| Advanced lexis: C1; C2 (% words per text) | 7.82 | 1.59 | 9.29 | 1.89 | 10.01 | 1.28 |

| Note: Platform 1, N = 150, n = 50 courses at each educational level. |

As can be seen in Table 3, among the courses at the three educational levels Level 3 courses have the highest average sentence length, highest average word length, contain more words of lower frequency and use more advanced lexis.

Results produced by the readability formulas also indicated a progression of text difficulty between the three levels.

Both Level 3 and Level 2 courses were assigned to the college level and were estimated as ‘difficult to read’.

However, the scores for Level 2 courses indicated easier readability than Level 3 courses: the average score for Flesch Reading Ease for Level 3 was 36.50, and for Level 2 it was 42.88.

Level 1 courses were estimated as suitable for 10th-12th grade and ‘fairly difficult to read’ with the average score for Flesch Reading Ease at 51.23.

The remaining three variables indicated some progression of linguistic complexity between Level 1 and Level 3 courses, but not between Level 2 and Level 3, as demonstrated in Table 4 below.

Table 4. Readability metrics: no salient difficulty progression between levels the educational levels of the courses under study

| Variables | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Type/token ratio | .18 | .04 | .2 | .04 | .2 | .03 |

| Noun elements per sentence (% elements per sentence) | 1.85 | .52 | 2.27 | .62 | 2.24 | .60 |

| Logical connectives (% per text) | 1.15 | .30 | 1.11 | .23 | 1.14 | .24 |

| Note: Platform 1, N = 150, n = 50 courses at each educational level |

As can be seen in Table 4, Level 1 courses contain slightly fewer unique words. They also have a greater repetition of words, contain fewer noun elements and have more cohesion between/within the sentences than the courses at Level 2 and Level 3.

At the same time, this progression was not observed between Level 2 and Level 3. The latter variable, logical connectives in the text, showed very small values in all three educational levels. This indicates that even the Introductory courses do not often use cohesion cues between/within the sentences in the texts.

Conclusion

The study concluded that most OER courses in English in their current form might not be accessible to non-native English readers who do not speak English fluently.

The study further concluded that the progression of text difficulty between more advanced courses was not clearly observed in the course sample.

At the same time, since the educational levels assigned to the OER courses suggest the order in which these courses should ideally be followed, their text difficulty should be expected to vary.

In contrast to this expectation, this study yielded no systematic differences in text difficulty across the different educational levels of the courses.

Implications for doing a comparative readability analysis with Text Inspector

The use of Text Inspector in the study of Rets et al. (2020) enabled the authors to make a case for raising the awareness of OER educators about the current difficulty level of English language OERs.

Educators should also pay greater attention to the meaning of current groupings of courses into educational levels on OER platforms. They should also pay more attention to the use of cohesion features, particularly in the texts of the courses that are assumed to be easier.

Rets et al. (2020) highlighted several advantages of using Text Inspector in comparative readability analyses. This can be summarised to the following points:

- Text Inspector provides the means to make conclusions on text readability based on a wide range of metrics.

- It aligns with the most recent research on the text features that have been shown to impact text comprehension, such as text cohesion, which is often ignored in readability studies.

- It is tailored to the field of English language learning and teaching. It provides additional scores that estimate the level of English language proficiency required for a non-native English reader to understand a given text in English.

- It allows for the analysis of courses on a large scale in a relatively short time frame.

Biography

Dr Irina Rets is a Research Associate at Lancaster University. She obtained her PhD in educational technology and Applied Linguistics from the Institute of Educational Technology at the Open University. In her PhD, she conceptualised and tested strategies for better accessibility of reading materials to international learners.

For more details about the study described here, see:

- Rets, I., Coughlan, T., Stickler, U., & Astruc, L. (2020). ‘Accessibility of Open Educational Resources: how well are they suited for English learners?’ Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 1-20. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2020.1769585.

- Rets, I. (2021). ‘Linguistic accessibility of Open Educational Resources: Text Simplification as an aid to non-native readers of English.’ (Doctoral dissertation, The Open University). doi: 10.21954/ou.ro.00012584

How to use Text Inspector to analyse your text in English

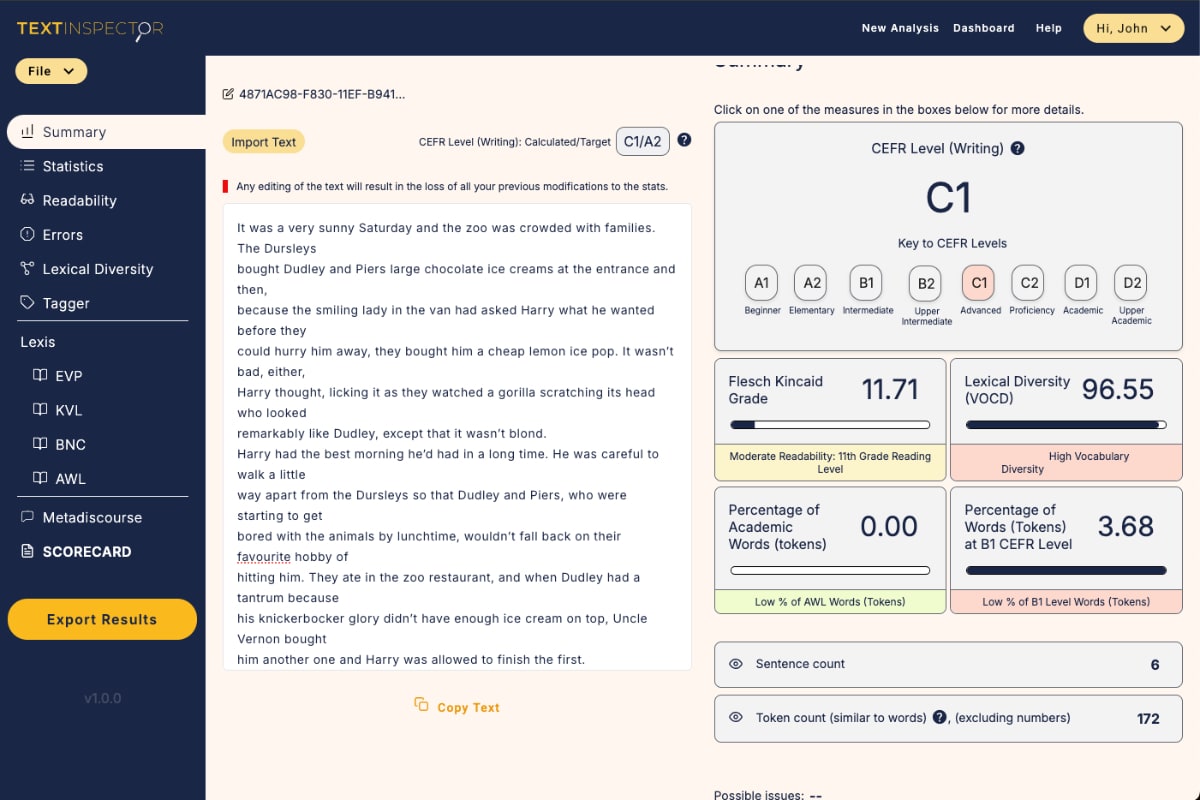

With Text Inspector, you can analyse texts of up to 250 words for free.

Simply head to the workflow page, copy your text and paste it into the search box. If you’d prefer, you can also upload your text directly to the page.

Next select writing, reading or listening and click the ‘analyse’ button. You’ll be taken to a summary page with an overview of the analysis including sentence count, readability, token-type ratio and syllable count.

We have designed Text Inspector to be as simple or complex as you need.

For more detailed information, you can click the menu options on the left side of the page and find out more about what the metrics mean by heading to our features pages.

You can also watch our helpful YouTube video: How to Use Text Inspector in Under 4 Minutes here.

To analyse longer texts, download your data or access the English Vocabulary Profile, Academic Word List or Scorecard, simply upgrade to one of our affordable subscriptions. We have options for individuals and organisations of all sizes.

Analyse a text in English with Text Inspector

Use Text Inspector to analyse a text in English and you can gain a real insight into English language use and optimise your understanding, learning and teaching of the language.

Try the Text Inspector tool today or find out more about our affordable subscription options here.

Share

Related Posts

Using Authentic Materials in Foreign Language Teaching: How Text Inspector Can Help

23 June, 2022

As an English language teacher, you’ve no doubt come across a wide variety of different […]

Read More ->

Lexical Diversity: An Interview with Aris Xanthos

23 June, 2022

Aris Xanthos is a lecturer and researcher in Humanities Computing at the University of Lausanne, CEO […]

Read More ->

Announcing the New and Improved Text Inspector 2.0!

5 March, 2025

We’re thrilled to announce the upcoming launch of the new and improved Text Inspector! This […]

Read More ->